The Space Movement:

Space Settlement and the Environment Space Settlement and the Environment

Space development has been good for the environment. It was a satellite that detected the ozone hole in the atmosphere, and today that hole is shrinking. It was satellite photos of the massive destruction of the Brazilian rain forest that convinced their government to pass laws to protect the Amazon Basin. A fleet of dozens of Earth-observing satellites are filling data archives with the information needed to understand the land, sea, air, and ecosystems of the only place in the universe that we know life exists: a thin layer on the outside of the third planet circling the Sun, just one of hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, which is just one of 80 billion galaxies in the observable universe.

These space technologies have been invaluable to the environment, and the future looks even more promising. Sixty-five million years ago, an asteroid slammed into Earth, exterminating the dinosaurs and nearly every living thing in an environmental catastrophe dwarfing anything mankind could do. Today, we are systematically finding small near Earth objects that would cause “only” regional devastation to our planet, and we have ideas about how to deflect any that might head our way. Unless there is a major asteroid strike in the near future, the one that destroyed the dinosaurs may be the last.

Energy use is another area where space development promises to improve our lives. Today, energy use lifts our standard of living but degrades our environment. One day, spacebased solar power may provide an ample supply of clean, reliable, predictable electrical energy. Scientists envision that giant spacecraft would collect energy and transmit it to Earth with no CO2 emissions—indeed, with no emissions of any kind. If the infrastructure for a space-based solar power system were built from lunar materials (difficult but entirely possible), this form of energy might be the cleanest available on a large scale, and it could last for billions of years.

However, Earth-observing satellites, planetary defense, and space-based solar power are not space settlement. What is the relationship between space settlement and the environment?

Space settlement is life’s next step. Life has always expanded through time and space, creating the conditions for its own existence. Our oxygen-rich atmosphere was created and is sustained by life itself. All vigorous ecosystems are constantly expanding, pushing outward to make more room for themselves. That’s why plants and animals dragged themselves out of the sea and onto land millions of years ago. Life is poised to expand once again, but this time it will expand from our beautiful but tiny sphere into the infinitely larger canvas of space.

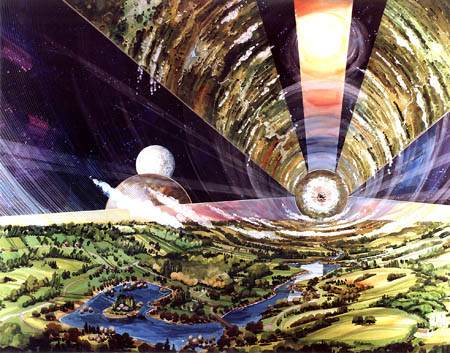

Mars and the Moon typically take center stage in discussions of space settlement, but their combined surface area is only about one-third that of Earth. In contrast, the materials in the single largest asteroid (Ceres) could be converted into space settlements with a combined living area between 100 and 1,000 times the surface area of Earth. Each of those millions of settlements would be a giant spacecraft housing tens of thousands of people in a separate, closed ecosystem. Their relatively small size would make environmental accountability quick: if the occupants of a settlement failed to follow sound environmental practices, their home would rapidly degrade and become unlivable, but this would not affect other settlements, giving life redundancy and resiliency.

Space settlement will give life what it lacks today: room to grow without degradation of the home planet. Space development can thus go far beyond preserving and restoring life on Earth. It can extend life throughout the cosmos. Think about that next time you look up at the stars.

This article was written by Al Globus, who has been a space settlement enthusiast since 1979. He is currently a member of the NSS Board of Directors and is a founder of the annual NASA/NSS Student Space Settlement Design Contest. The article originally appeared in Ad Astra, Winter 2009.