By K. Eric Drexler

From L5 News, May 1981

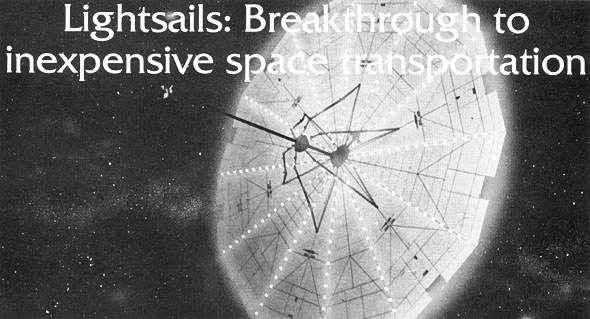

Light sails of the future may appear like this Brian Sullivan rendering based on designs by the Jet Propulsion Laboratories. K. Eric Drexler, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Space Studies Center and L-5 Board member, submitted this report to OMNI for inclusion in the “prospectus on space” they are preparing.

In space, rockets have propelled past vehicles, typically burning fuel many times more massive than the vehicle itself. Since this fuel has been launched from Earth at great expense, the cost of transportation from orbit to orbit in the solar system has been high, typically thousands of dollars per pound. This high cost has kept deep space a purely academic preserve.

Lightsails are a class of solar sail that would build on work done at JPL and on planned space processing capabilities to produce a superior vehicle. They would need no fuel, relying instead on the pressure of sunlight on large, thin sheets of aluminum to propel the vehicle. Such a vehicle could travel from any orbit in the Solar System to any other, so long as it kept from coming too close to the Sun or planetary atmospheres. In a day, a Lightsail could supply as much thrust as could be obtained by burning an equal mass of rocket fuel. The next day, when the rocket fuel would be gone, the sail could do it again, then continue day in and day out for years. Such a sail could reach Mars in about 100 days, more than twice as fast as an ordinary rocket.

Lightsails would gain this remarkable performance by using thin metal films made in space (they have been made on Earth, but are too delicate to launch and unfold). Cost estimates remain rough, but seem to indicate that a machine to make Lightsails could be developed for less than a billion dollars, and that the sails could be made (in bulk) for around 10 cents per square meter, about the cost of household aluminum foil, though much thinner. At this cost, a sail could transport material from the nearest asteriods for less than a dollar a kilogram.

Thus, through eliminating the need for expensive fuel, Lightsails offer the prospect of reducing the cost of deep space transportation by a factor of 1,000 or more. This prospect demands reconsideration of the practicallity of using space resources. Consider: How much mining and trucking would be done if fuel cost not $1, but $1,000 per gallon? How much weight, then, should be given to past assumptions about what is and is not practical in space?

Many asteriods contain steel alloyed with nickel, cobalt, and platinum group metals. Nickel and cobalt are imported strategic materials, costing about $5 and $10 per kilogram, respectively. The platinum group metals find use throughout technology, and are produced almost exclusively by South Africa and the Soviet Union. Asteriodal resources could be recovered, initially, by devices no more complex than those proposed for automatic sample return from Mars. Launching material into space is expensive, but returning material is all downhill.

Although lightweight, Lightsails would be large. Thus far, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. have only launched starlike dots into the sky; Lightsails seem an obvious next step, and would be the first new objects with a distinctly visible shape to enter the night sky in human history.

According to an in-house review, NASA considers Lightsails “highly promising”. Unfortunately, NASA has thus far failed to consider Lightsails together with their primary applications, and has merely concluded that they might cost too much to develop, given only the failing planetary science program as a justification. Since they would find far greater application in transportation of satellites to geosynchronous orbit, or in recovery of materials from asteriods, the agency needs to take a second look. The promise of Lightsails appears to warrant at least a serious consideration of their applications to planned programs, and to the new projects they can make feasible, as well as funding for low-cost exploratory experimentation. Since this concept originated outside government and industry, in a university, it badly needs advocates within the system. Since the first steps need very little money, beginning work on Lightsails would be a major step toward a new space program of great potential benefit, yet a step with little budgetary effect.